Rocketbuilding Part 1.

Why I started again. Again.

So, I’ve just got back to my apartment after a weekend watching rockets rip off into the midlands sky. I’ve glanced over to my little pile of in-progress rockets and a thought has struck me. “These can’t be safe”

It’s back in November and I’ve already decomissioned one of my rocket projects. There’s good reasons for that. I didn’t really think ‘too light’ would be a problem until the crunch-time came. 3 days before launch I look at the altitude limits and realise I’ve either got to figure out how to make this do something mad with dual deployment, or make it a lot heavier. Unfortunately, I don’t have the steel and at that time I didn’t have either the circuitry or the embedded systems knowledge to make my own electronic deployment system. Lets not even mention the cost of parachutes. So, time for a new phase of design. A lesson in checking your design requirements thoroughly before getting started.

The launch gets cancelled anyway. At least I got all these pretty pictures of the development.

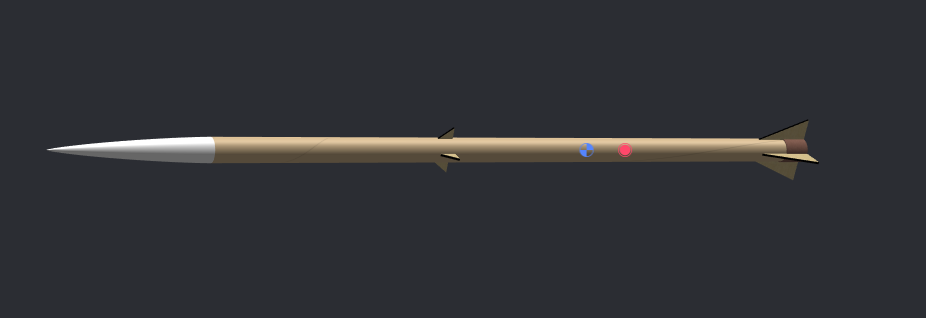

A few months have gone by and over the winter I threw together a little minimum-diameter rocket. 29mm minimum diameter, too. If I put a decent motor in this it’ll go faster than anything I’ve seen before. That’s pretty handy. I’ve not gone as simple as I could have. There’s a little space for some avionics when I finally get round to wiring them all up and 3D-printing a little enclosure.

The body is kraft phenolic. A nice little resin. It’s strong as all hell, if a little brittle. The same could be said about the little fins on here. PLA prints, held on by some epoxy. It’s the same PLA for the nosecone too. I’ve checked the stability numbers. Openrocket tells me 1.75cal. Dead in the middle, with a G motor. Right where I want it. I can also put a lighter motor in, and it doesn’t reach much further than 2.5cal. Neat.

What’s all this about stability and G motors? Stability, here, is the ability for the rocket to passively right itself during flight. When wind pushes against it and moves it off its angle of flight, the stability number will tell you how it responds to this. It’s measured in calibers, or cal. One caliber is equal to the diameter of the body. Why is stability a distance unit? It represents how far the centre of gravity is ahead of the centre of pressure. Numbers in the range 1.5-2cal are desirable. The rocket will achieve a nice balance here. Any lower and it might not fly straight, too high and it’ll overcorrect in wind. G is just the impulse class of the motor, how much oomf it has, if you like. Bigger letters, more overall momentum imparted to the rocket in a flight.

Ok so we know that maths says it’ll fly. What about launching and recovery? The forward assembly has a solid O-ring for the parachute and there’s a little collar on the inside that’s made of delrin and has a bolt running throught it. I just attach the other side of the parachute to that and it’ll all go up and down safely. Right? Rigggghhhht???

I decide to just take in the weather and watch some launches this weekend, I’m not in a rush, I’ll work the rocket project for next month and launch then. I stand around in the sun, talk to my friends, and watch dozens of launches flick by. Taking a few pretty photos in the process.

Now, it’s time for my girlfriend to launch. She’s 3D-printed the entire lower assembly of her rocket. The fins are replaceable and it all just screws together without glue or bolts, or any captive parts. (As a note to her: Babes, this is actually really impressive). It’s sitting on the rod now. We take a small pause and with a little stamp on the ignition, the engine starts to burn with a soft roar. It begins to slip upwards and off the aluminium launch rod. Then, we watch this threat piroutte terrifying loops about 4m above our heads (and again on the second launch).

So again, we’re returned to my apartment and I’m sitting on my bed. I’m looking at my little pile of parts (all good rocket makers have a pile). The thought occurs. These can’t be safe.

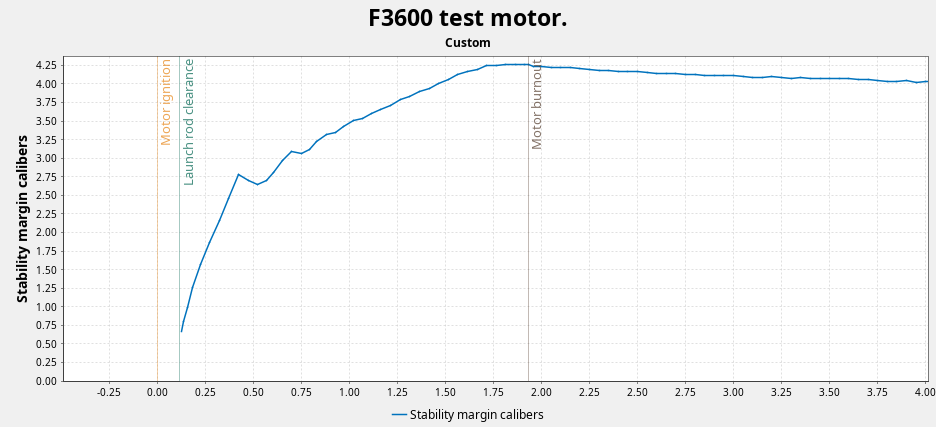

The lesson we’ve just learned, ladies and children, is about something I’ve learned is termed off-rod stability. Remember those little numbers I mentioned. Wasn’t that a pretty little picture of how things worked? Rockets have a big number that tell you that they’re safe to lauch, great. Unfortunately not. You see the stability of a rocket is very dependent on how fast it’s moving, or rather the flow of air moving over it. That determines the centre of pressure, after all. If it’s not moving fast enough it wont be stable, and it could go where it likes. Hell, if it’s too fast it could get too stable, or too unstable. Aerodynamics above Mach 0.6 can get a little complicated. But anyway, that’s the real point of a launch rod. It’s not there to hold the rocket in place for launch and point it in a nice direction (although these are important features). In my strong opinion, the first purpose of the launch rod is to keep your rocket along a stable flightpath while it accelerates enough to enter a safe stability region. Hopefully it stays there for the rest of the flight.

Let’s check OpenRocket. Here she is. Her name is Assegai.

She’s a minimum diameter build, and the first one I’ve actually constructed. Look at those little fins. Cute, eh? 1.87cal, too. On the nice side of that stability range. Not overstable, not understable. Just right. She’ll also come off the launch rod at about 19m/s. I’ve always been told that’s fast enough. I wonder what happens if we skip the summary numbers and look at the stability across the whole flight of a test motor?

Seems I’ve fallen for the same problem. This little 1km altitude rocket becomes wildly overstable later in flight (time on the x-axis). Not only that but for about 0.125s this rocket has an average stability of 1cal. The lowest stability I’ve ever seen a rocket launched was hitting 1.4cal off the rod. Now I’m not saying this design is dangerous. However, if you were throwing something into the sky at half the speed of sound, would you cross a safety margin? Time for a redesign :)